The laws of Physics

There are the laws of men, and the laws of nature. The latter cannot be broken. Dura lex, sed lex! At human scale, a few parameters dominate almost everything.

Mass matters everywhere

Weight drives almost everything: the resources needed to build a vehicle, the energy required for every acceleration, climb, or stop.

It increases rolling resistance, amplifies non-exhaust pollution, and multiplies the energy involved in crashes.

Reducing mass is one of the most effective ways to reduce environmental and safety impact across the system.

Higher mass requires heavier tires, often with worse rolling resistance, which compounds the inefficiency.

Speed is expensive

Aerodynamic drag grows with the square of speed, and the power required to overcome it grows with the cube. Some automakers historically ignored aerodynamics, hoping to brute-force physics with bigger engines. As Enzo Ferrari famously quipped:

“Aerodynamics are for people who can’t build engines.”

We can now gently remind Signor Ferrari that drag grows with the square of speed, engine power grows linearly at best, and thus, horsepower cannot escape air resistance. Shape and frontal area matters more.

Aerodynamics matter sooner than intuition suggests

At 20–30 km/h, drag dominates rolling resistance aldready.

Frontal area, flow separation, and shape are just as important as drivetrain efficiency.

Lightweight, slender designs reduce energy use before even touching the question of energy storage.

Powertrain efficiency

Thermal engines are inherently limited: about 20% efficient at best.

Electric motors can exceed 80% efficiency, dramatically reducing the energy cost per kilometer.

But as we saw with EV, power train efficiency alone does not solve the issue.

Plus rebound effect for the embodied energy required by the now even heavier and ressource intensive vehicle mitigate a lot of the benefit…

Safety

Imagine driving a tank: you may feel invincible inside, but everyone around you is in danger.

A heavier car may protect its occupants, but collisions with lighter vehicles or users transfer enormous energy.

Since collision energy grows with mass and the square of speed, speed matters more than mass.

Designing for safety is therefore an ethical as well as technical problem:

we cannot optimize only for occupants without considering others.

Range and energy storage

Batteries are not perfect, they are like chemotherapy: not harmless, but necessary in some context.

The “poison” is proportional to how much you carry. Massive batteries increase rare-earth extraction, weight penalties, and inefficiency.

Range should be treated realistically. Most daily trips are 20 to 50 km.

We can design batteries for that reality, smaller, lighter, more repairable, because our vehicle efficiency drastically reduces energy needs.

Other storage ideas deserve exploration too like compressed air or simpler chemistries to fully remove the conflicts mineral from the equation.

“Newton’s third law, the only way humans have ever figured out of getting somewhere is to leave something behind.” - TARS, Interstellar Whether it’s a horse on a military campaign or a spaceship in orbit, the further one want to go, the more fuel, or food it need to carry, which in return increase the consumption. It’s not rocket science… though in rocketry, it’s formalized as the Tsiolkovsky rocket equation.

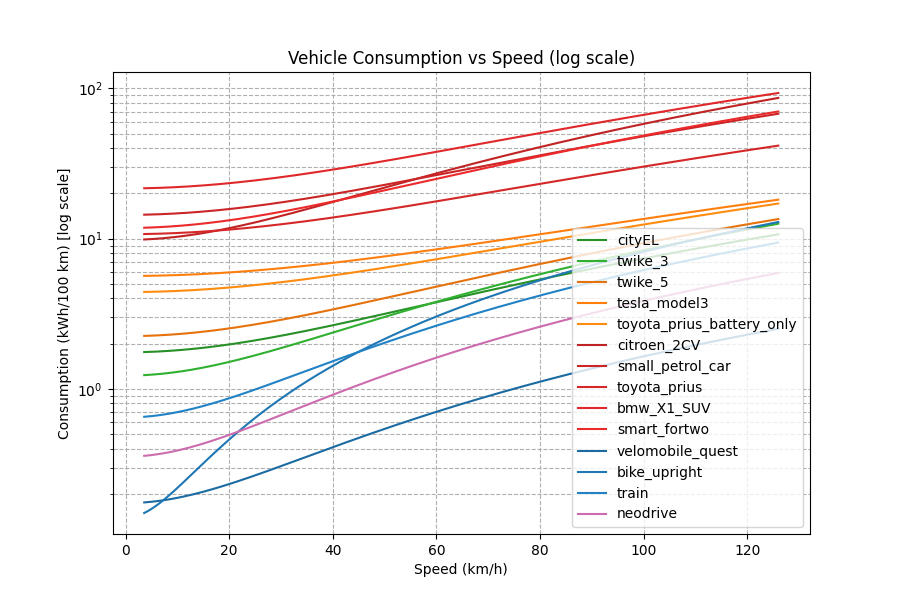

This plot illustrates how energy consumption varies with speed across a range of vehicles. Modern petrol cars, like a typical hatchback, and historical models, such as the Citroën 2CV, show high energy use at even moderate speeds. We can see that in the decades between the 2CV and modern petrol car, little to no progress was made efficiency wise. Electric cars, such as a Tesla Model 3 or a Prius in electric mode, achieve lower energy per kilometer, but the gain are relatively modest in the order of 3-5 time. One the other hands, light vehicles, like the CityEL or the Twike which where designed almost 50 years ago, sit far below conventional and electric cars in energy use, especially at urban speeds (20–50 km/h). This prove that efficiency is not a matter of technology but toughtful design. Trains also show strong efficiency at higher speeds due to reduced rolling resistance and the fact that the aerodynamic drag is compensated by the very large number of people it can move at once but this vary wildly with the train occupation.

This plot highlights a fundamental insight: vehicle mass and aerodynamics dominate energy consumption, and lighter, streamlined designs achieve massive efficiency gains before even considering the type of powertrain. It emphasizes why reducing weight and frontal area is critical for sustainable mobility, particularly for city travel where conventional cars are extremely overpowered for the task.

If you want a more in-depth overview, the first chapters of this document might interest you